Books About Residential Schools for Kids of All Ages

The last residential school in Canada closed in 1996 but, chances are, even if you were attending school at that time, you would not have heard of residential schools, nor the shocking and painful history behind them. Although 130 residential schools were in operation in Canada over more than 100 years, it wasn’t until 2015, when the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada concluded its mandate to inform all Canadians about what happened in residential schools, that most Canadians started to learn about the atrocities committed by the Canadian government and associated religious institutions to Indigenous, First Nations, Métis, and Inuit children and their families.

In a nutshell, the children were (often, forcibly) removed from their families to live in the residential school. They were forbidden to speak their languages or participate in their cultures in any way. They were isolated from their families and communities and often physically and sexually abused.

Most of us didn’t learn about this in school. So, as parents, it’s a daunting subject to tackle with our own children. Here are some books that can help to inform and educate in an age-appropriate ways:

Books About Residential Schools for Children 4-10 years of age

The Boy Who Walked Backwards

By Ben Sures

Based on a true story about the father of one of author Ben Sures’ friends, The Boy Who Walked Backwards is the story of Leo, a young Ojibway boy, and his family in Serpent River First Nation. Leo’s life turns to darkness when he’s forced to attend residential school. While at home for Christmas, Leo uses inspiration from an Ojibway childhood game to deal with his struggles.

Not My Girl

By Christy Jordan-Fenton & Margaret-Olemaun Pokiak-Fenton

Based on the true story of Margaret Pokiak-Fenton, Not My Girl makes the original, award-winning memoir, A Stranger at Home (see below), accessible to younger children. It is also a sequel to the picture book When I Was Eight (see below). It’s a poignant story of a determined young girl’s struggle to belong. Margaret’s homecoming is not what she expected. Two years ago, she left her Arctic home for the residential school. But upon her return her mother stands still as a stone. This strange, skinny child, with her hair cropped short, can’t be her daughter. “Not my girl!” she says angrily. Margaret’s years at school have changed her. Now ten years old, she has forgotten her language and the skills to hunt and fish. She can’t even stomach her mother’s food. Her only comfort is in the books she learned to read at school. Gradually, Margaret relearns the words and ways of her people.

Phyllis’s Orange Shirt

By Phyllis Webstad

Phyllis’s Orange Shirt is an adaptaion of The Orange Shirt Story which was the best selling children’s book in Canada for several weeks in 2018. This true story also inspired the movement of Orange Shirt Day which could become a federal statuatory holiday. When Phyllis was a little girl she was excited to go to residential school for the first time. Her Granny bought her a bright orange shirt that she loved and she wore it to school for her first day. When she arrived at school her bright orange shirt was taken away. This is both Phyllis Webstad’s true story and the story behind Orange Shirt Day which is a day for everyone to reflect upon the treatment of First Nations people and the message that ‘Every Child Matters’.

Shi-shi-etko

By Nicola I. Campbell

In just four days young Shi-shi-etko will have to leave her family and all that she knows to attend residential school.

She spends her last days at home treasuring the beauty of her world — the dancing sunlight, the tall grass, each shiny rock, the tadpoles in the creek, her grandfather’s paddle song. Her mother, father, and grandmother, each in turn, share valuable teachings that they want her to remember. And so Shi-shi-etko carefully gathers her memories for safekeeping.

Shi-shi-etko is a moving and poetic account of a child who finds solace all around her, even though she is on the verge of great loss — a loss that native people have endured for generations because of the residential schools system.

The Train

By Jodie Callaghan

The Train is the story of how Ashley met her great-uncle by the old train tracks near their community in Nova Scotia. He tells her that during his childhood the train would bring their community supplies, but there came a day when the train took away with it something much more important. One day he and the other children from the reserve were taken aboard and transported to residential school, where their lives were changed forever. They weren’t allowed to speak Mi’kmaq and were punished if they did. Uncle tells her he tried not to be noticed, like a little mouse, and how hard it was not to have the love and hugs and comfort of family. He also tells Ashley how happy she and her sister make him. They are what give him hope. Ashley promises to wait with her uncle as he sits by the tracks, waiting for what was taken from their people to come back to them.

When I Was Eight

By Christy Jordan-Fenton & Margaret-Olemaun Pokiak-Fenton

Based on the true story of Margaret Pokiak-Fenton, When I Was Eight is a version of Fatty Legs (see below) that is reimagined for younger readers. Olemaun is eight and knows a lot of things. But she does not know how to read. Ignoring her father’s warnings, she travels far from her Arctic home to the outsiders’ school to learn.

The nuns at the school call her Margaret, cut off her long hair, and force her to do menial chores. But Margaret remains undaunted, even in the face of the black-cloaked nun who tries to break her spirit at every turn. But the young girl is more determined than ever to learn how to read.

When We Were Alone

By David A. Robertson

A young girl helps tend to her grandmother’s garden and begins to notice things about her grandmother that make her curious. Why does her grandmother have long braided hair and wear beautifully coloured clothing? Why does she speak another language and spend so much time with her family? As she asks her grandmother about these things, she is told about life in a residential school a long time ago, where everything was taken away. When We Were Alone is a story about a difficult time in history and, ultimately, a story of empowerment and strength.

Books About Residential Schools for Children 7-11 years of age

As Long as the Rivers Flow

By Larry Loyie

As Long as the Rivers Flow is the story of Larry Loyie’s last summer before entering residential school. It is a time of learning and adventure. He cares for an abandoned baby owl and watches his grandmother make winter moccasins. He helps the family prepare for a hunting and gathering trip.

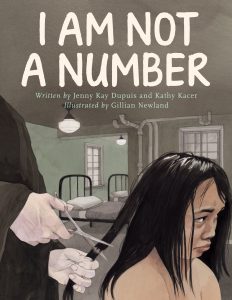

I Am Not a Number

By Jenny Kay Dupuis & Kathy Kacer

In I Am Not a Number, eight-year-old Irene is removed from her First Nations family to live in a residential school and she is confused, frightened, and terribly homesick. She tries to remember who she is and where she came from, despite the efforts of the nuns who are in charge at the school and who tell her that she is not to use her own name but instead use the number they have assigned to her. When she goes home for summer holidays, Irene’s parents decide never to send her and her brothers away again. But where will they hide? And what will happen when her parents disobey the law?

Shin-chi’s Canoe

By Nicola I. Campbell

A sequel to the award-winning Shi-shi-etko, Shin-chi’s Canoe tells the story of Shi-shi-etko’s six-year-old brother, who is joining Shi-shi-etko at residential school. They begin their journey in the back of a cattle truck, and Shi-shi-etko tells her little brother all the things he must remember: the trees, the mountains, the rivers, and the tug of the salmon when he and his dad pull in the fishing nets. Shin-chi knows he won’t see his family again until the sockeye salmon return in the summertime.

When they arrive at school, Shi-shi-etko gives him a tiny cedar canoe, a gift from their father. The children’s time is filled with going to mass, school for half the day, and work the other half. The girls cook, clean, and sew, while the boys work in the fields, in the woodshop, and at the forge. Shin-chi is forever hungry and lonely, but, finally, the salmon swim up the river and the children return home for a joyful family reunion.

Books About Residential Schools for Children 9-12 years of age

Dear Canada: These Are My Words: The Residential School Diary of Violet Pesheens

By Ruby Slipperjack

Inspired by her own experience at residential school, author Ruby Slipperjack introduces us to Violet Pesheens, who is struggling to adjust to her new life. In Dear Canada: These Are My Words, Violet misses her Grandma; she has run-ins with Cree girls; at her “white” school, everyone just stares; and everything she brought has been taken from her, including her name—she is now just a number. But worst of all, she has a fear. A fear of forgetting the things she treasures most: her Anishnabe language; the names of those she knew before; and her traditional customs. A fear of forgetting who she was.

Her notebook is the one place she can record all of her worries, and heartbreaks, and memories. And maybe, just maybe, there will be hope at the end of the tunnel.

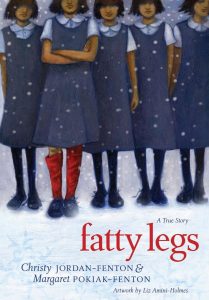

Fatty Legs: A True Story

By Christy Jordan-Fenton & Margaret-Olemaun Pokiak-Fenton

In Fatty Legs: A True Story, eight-year-old Margaret Pokiak is determined to learn how to read, even though it means leaving her village in the high Arctic. Her father finally agrees to let her make the five-day journey to attend school, but he warns Margaret of the terrors of residential schools.

At school Margaret is treated cruelly by Raven, a black-cloaked nun with a hooked nose and bony fingers that resemble claws. But Margaret refuses to be intimidated and bravely stands up for herself this is an inspiring first-person account of a plucky girl’s determination to confront her tormentor.

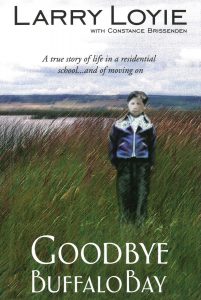

Goodbye Buffalo Bay

By Larry Loyie

The sequel to the award-winning book As Long as the Rivers Flow and the award-finalist When the Spirits Dance, Goodbye Buffalo Bay is set during the author’s teenaged years. In his last year in residential school, Lawrence learns the power of friendship and finds the courage to stand up for his beliefs. He returns home to find the traditional First Nations life he loved is over. He feels like a stranger to his family until his grandfather’s gentle guidance helps him find his way. Lawrence fights a terrifying forest fire, makes his first non-Native friends, stands up for himself in the harsh conditions of a sawmill, meets his first sweetheart and fulfills his dream of living in the mountains. Wearing new ice skates bought with his hard-won wages, Lawrence discovers a sense of freedom and self-esteem. Goodbye Buffalo Bay explores the themes of self-discovery, the importance of friendship, the difference between anger and assertiveness, and the realization of youthful dreams.

My Name Is Seepeetza

By Shirley Sterling

At six years old, Seepeetza is taken from her happy family life on Joyaska Ranch to live as a boarder at the Kalamak Indian Residential School. Life at the school is not easy, but Seepeetza still manages to find some bright spots. Thoughts of home make her school life bearable. My Name Is Seepeetza is an honest, inside look at life in an Indian residential school in the 1950s, and how one indomitable young spirit survived it.

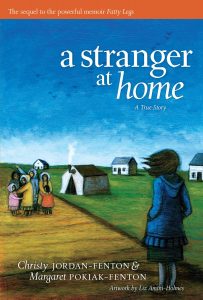

A Stranger at Home

By Christy Jordan-Fenton & Margaret-Olemaun Pokiak-Fenton

Based on her own life, 10-year-old Margaret Pokiak is traveling to be reunited with her family in the arctic. Two years ago, her parents delivered her to the school run by the dark-cloaked nuns and brothers. She spots her family, but her mother barely recognizes her, screaming, “Not my girl.” Margaret is now marked as an outsider and she feels like. She no longer remembers the language and stories of her people, and can’t stomach the food her mother prepares. However, Margaret gradually relearns her language and her family’s way of living. A Stranger at Home is the sequel to Fatty Legs.

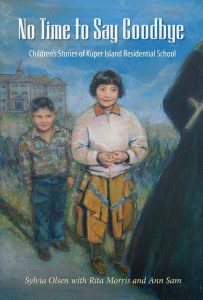

No Time to Say Goodbye: Children’s Stories of Kuper Island Residential School

By Sylvia Olsen with Rita Morris & Ann Sam

No Time to Say Goodbye is a fictional account of five children sent to aboriginal boarding school, based on the recollections of a number of Tsartlip First Nations people. These unforgettable children are taken by government agents from Tsartlip Day School to live at Kuper Island Residential School. The five are isolated on the small island and life becomes regimented by the strict school routine. They experience the pain of homesickness and confusion while trying to adjust to a world completely different from their own. Their lives are no longer organized by fishing, hunting and family, but by bells, line-ups and chores. In spite of the harsh realities of the residential school, the children find adventure in escape, challenge in competition, and camaraderie with their fellow students.

Speaking Our Truth: A Journey of Reconciliation

By Monique Gray Smith

In Speaking Our Truth: A Journey of Reconciliation, author Monique Gray Smith explores the historic relationship between Indigenous Peoples and non-Indigenous people in Canada, the legacy of the Indian Residential School system, and the impact still being felt by survivors and their families. Readers will learn how Canadians can move forward with reconciliation.

Books about Residential Schools for Kids Ages 13 and up

Broken Circle, The Dark Legacy of Indian Residential Schools: A Memoir

By Theodore Fontaine

Broken Circle is the true story of Theodore Fontaine, who lost his family and freedom just after his seventh birthday, when his parents were forced to leave him at an Indian residential school by order of the Roman Catholic Church and the Government of Canada. Twelve years later, he left school frozen at the emotional age of seven. He was confused, angry and conflicted, on a path of self-destruction. At age 29, he emerged from this blackness. By age 32, he had graduated from the Civil Engineering Program at the Northern Alberta Institute of Technology and begun a journey of self-exploration and healing.

Good for Nothing

By Michel Noel

Good for Nothing takes place in 1959, fifteen-year-old Nipishish returns to his reserve in northern Quebec after being kicked out of residential school, where the principal told him he’s a good-for-nothing who, like all Indians, can look forward to a life of drunkenness, prison and despair. But the reserve offers nothing to Nipishish. He remembers little of his late mother and father. And he seems to know less about himself than the people at the band office. He must try to rediscover the old ways, face the officials who find him a threat, and learn the truth about his father’s death.

Sugar Falls: A Residential School Story

By David Alexander Robertson

Sugar Falls is the timeless graphic novel that introduced the world to the awe-inspiring resilience of Betty Ross, Elder from Cross Lake First Nation, and shared her story of strength, family, and culture.

A school assignment to interview a residential school survivor leads Daniel to Betsy, who tells him her story. Abandoned as a young child, Betsy was soon adopted into a loving family. A few short years later, at the age of 8, everything changed. Betsy was taken away to a residential school. There she was forced to endure abuse and indignity, but Betsy recalled the words her father spoke to her at Sugar Falls—words that gave her the resilience, strength, and determination to survive.

RELATED:

– How to Explain Reconciliation to Children

Fatty Legs: A True Story by Christy Jordan-Fenton & Margaret-Olemaun Pokiak-Fenton Had you read the Foreward of this book, you would know that this book should not be recommended for kids. Blaming “The whiite people” for horrible things they did? What does a child irregardless of colour think when reading this comment? Some of the so called “truth” is questionable given the time period.

“White people” is not a racist statement, it’s the truth.

Regardless, there’s no such thing as racism against white people.

Thank you for this list!

“My Fatty Legs” needs to be removed from the read list. The racist comment in the Foreword: “the white people did terrible things” is disgusting that in a multi-cultural society this book is on a recommended reading list for children.

Hard to explain that to the kid that lives in a multi-racial family with multi-cultural friends. Wrong word “racial prejudice” is still not acceptable reading for children.

Your multi-racial family with multi-cultural friends should understand that “white people” have always had privilege and with privilege comes power. By not acknowledging that, it completely devalues the prejudices that BIPOC people have faced and continue to face. To suggest it wasn’t and isn’t “white people” who are responsible for racism and discrimination, or that saying so is actually racist to say, takes the onus off of the very people who need to own up and fix things… “Truth and Reconciliation,” if you will…